Farming the Future

How Farm Mechanization Could Turn Bangladesh’s Youth Unemployment Crisis into Rural Opportunity

For 23-year-old Ali Ahmed, the rice paddies around his home in Ukhiya, Cox’s Bazar looked like a dead end. They represented a life of back-breaking, low-paying work — the same demanding labor his parents had always known. As a university student, his future felt trapped between two impossible choices: abandon his education to take up the family toil or abandon his home for an uncertain, low-wage job in a crowded city.

The crossroads Ali faced changed the day he attended a local demonstration for modern farm machinery. Where others saw just a machine, Ali saw a different future. He saw a business. Using a 70% government subsidy, Ali invested in a reaper and two rice transplanters.

Today, Ali is an entrepreneur with a successful mechanization service that provides high-tech planting and harvesting for over 60 acres in his community. His net income jumped 50% in the first year alone. Most importantly, he was still a student when he started. “Agriculture pays for my education,” Ali said.

Ali’s story is not a lucky exception. It is a blueprint. He is proof that the answer to Bangladesh’s youth unemployment challenge may not be in the cities but waiting in the fields.

Youth unemployment in Bangladesh is a critical socioeconomic challenge, characterized by significant urban-rural disparities, high underemployment, and widespread informality. While cities contribute nearly 89% of Bangladesh’s GDP, rural youth continue to face limited access to decent jobs and skills training. Agriculture, which employs over 40% of the workforce, remains the backbone of the rural economy. However, many young people are increasingly disengaged from agricultural work due to poor labor conditions, low wages, and limited development opportunities.

Amid these challenges lies an often overlooked solution: agricultural mechanization. Modernizing the sector and integrating agro-based industries can boost productivity while creating meaningful jobs for rural youth and women. Lessons from countries like Canada, India, and Nigeria offer a roadmap for transforming agriculture into a dynamic and appealing employment sector for young Bangladeshis.

Why Mechanization Matters for Youth and Rural Bangladesh

Mechanization is about more than just bigger tractors. It transforms the way agriculture is practiced by enabling faster land preparation, timely planting and harvesting, reduced drudgery, and greater scale and output. For youth, this shift opens up new opportunities as equipment operators, maintenance technicians, service providers, and logistics coordinators.

In Bangladesh’s context, where youth underemployment and informal work dominate in rural areas, mechanization can serve as a bridge. It not only creates demand for machinery but also for workers who can operate and maintain them, shifting labor from low-productivity roles to higher value employment.

The economic case for mechanization is clear. In parts of Bangladesh, data shows that adopting mechanized solutions leads to substantial cost savings compared to manual labor. For instance:

Power Tiller Operated Seeder (PTOS): Machine operation costs approximately $65–70 per hectare, representing a 45–50% saving over manual operations ($110–120).

Rice Transplanter: Excluding seedling costs, using a transplanter reduces expenses from about $200–205 to $140–145 per hectare, offering a benefit of $55–60 per hectare.

Reaper and Combine Harvester: These technologies offer significant savings, with benefits of $55–60 and $78–85 per hectare, respectively.

Lessons From Abroad

Canada

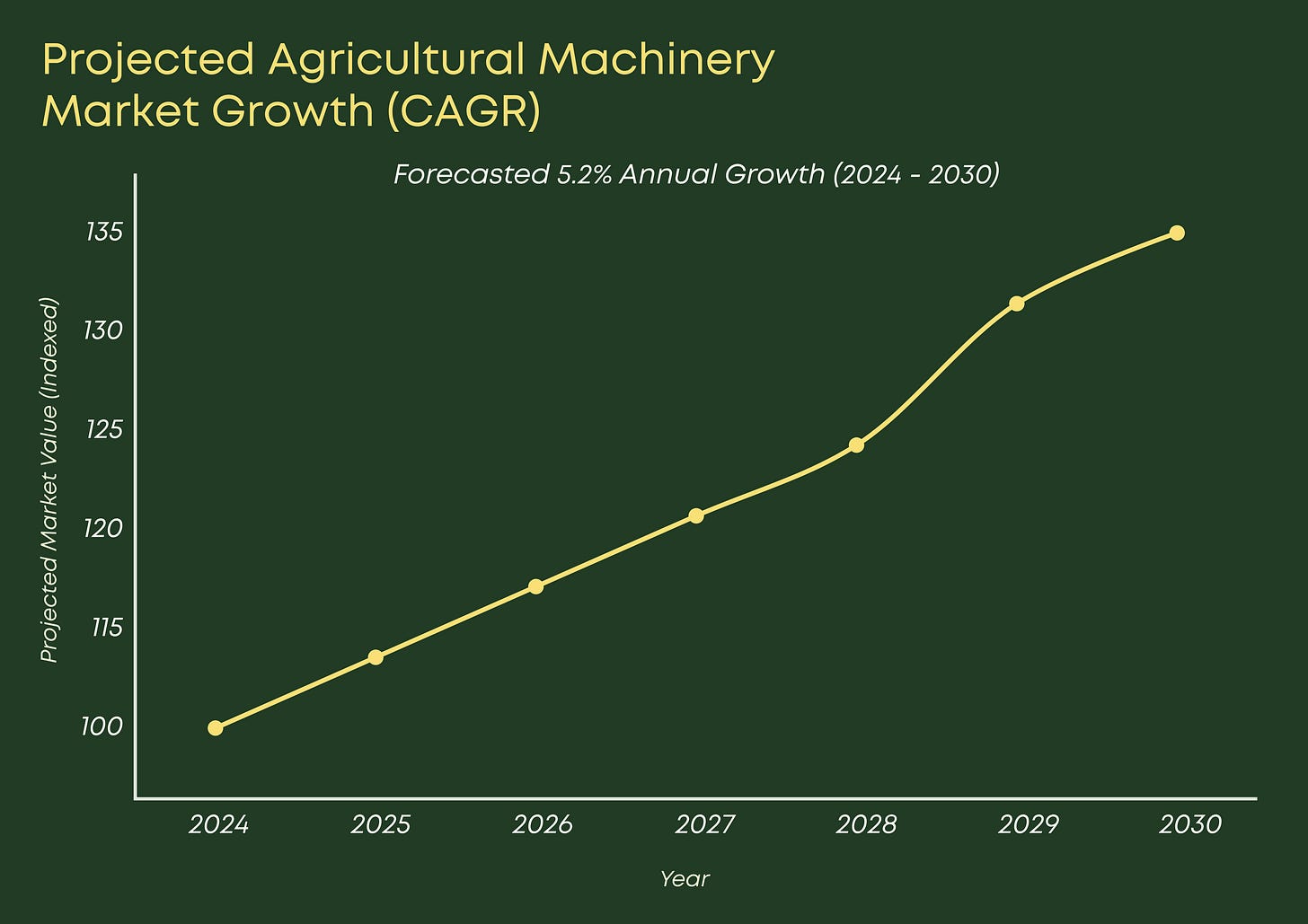

One of the world’s most mechanized farming systems, Canada shows what the mature end of the spectrum looks like. In 2023, Statistics Canada reported that 87% of Canadian farms are mechanized. Small and mid-power tractors dominate new purchases and the agricultural machinery market in Canada is forecasted to grow at a 5.2% CAGR through 2030.

The result is high productivity per hectare, fewer labor-intensive tasks, and greater demand for technicians, repair services, logistics and management roles. Canadian agriculture is rapidly adopting precision and digital technologies such as GPS-guided planters, smart sensors, and AI-driven systems to further improve efficiency and competitiveness. This focus on artificial intelligence, robotics, and big data is creating new, high-value career pathways across the agri-food sector. Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) promotes careers in science, engineering, and technology, while programs like the Youth Employment and Skills Program (YESP) provide youth with hands-on experience and help address the sector’s aging workforce. YESP offers up to $14,000 in matching funds for salary support, and up to $5,000 in additional support to offset employment barriers for disadvantaged youth. This approach helps younger people better understand modern agriculture and recognize its career potential.

India

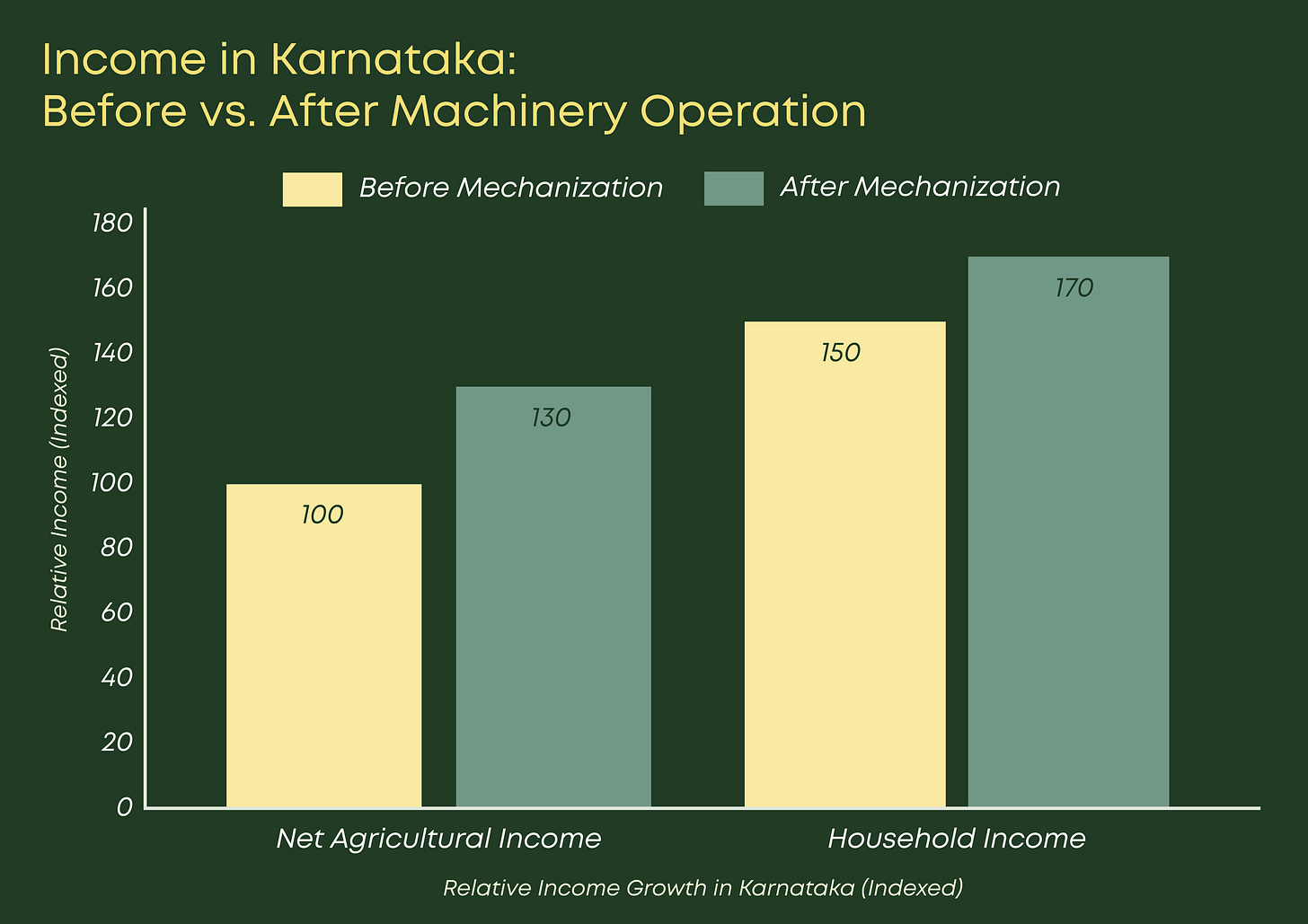

A large agrarian economy with millions of smallholders, India has developed mechanization models suited to fragmented land-holdings such as tractor-sharing, custom-hiring centres, and small implements. One manufacturer describes how mechanization service providers act as both owner-operators and service rental firms, increasing access to mechanized tools for smaller farms. The adoption of appropriate machinery, even in states like Karnataka where overall mechanization is around 27%, has shown positive growth in key crops like paddy and green gram. The adoption of machinery has been found to increase net agricultural income by 31% and household income by 19%.

India’s approach to mechanization, including the National Programme for Rural Industrialisation (NPRI) which aims to set up rural industrial clusters has generated full-time and semi-skilled jobs. Case studies, such as the Maharashtra Sugar Industry and the Amul Dairy Cooperative Movement, illustrate how these clusters build essential rural infrastructure (roads, irrigation) and guarantee stable employment and improved income for hundreds of thousands of rural workers and farmers, significantly enhancing women’s financial autonomy.

Nigeria

In sub-Saharan Africa, Nigeria embodies the risk of low mechanization. With a tractor density of just 0.27 hp/ha (far below the FAO recommended 1.5 hp/ha), Nigeria ranks 132nd out of 188 countries for mechanization. The Nigerian government has historically promoted mechanization through input subsidy schemes and specific incentives, including zero tariffs on agricultural machinery and equipment, and an aggregate 40% subsidy on tractors and implements.

The newly launched Global Agricultural Mechanisation Program is designed to empower mechanization service providers by deploying equipment, with the goal of generating over 2,000 agricultural jobs. A flagship program, the SAPZ initiative, backed by the African Development Bank (AfDB) and other partners, aims to create hubs that integrate production, processing, and distribution of crops and livestock. These zones are explicitly designed to empower farmers, especially women and youth, by creating sustainable markets, generating wealth, and reducing post-harvest losses, emphasizing on institutional capacity building, skills development, and private investment facilitation across value chains.

How Bangladesh Can Move from Policy to Action

To harness mechanization for youth employment and rural growth, Bangladesh must adapt from the lessons above while aligning with its unique context. The stories of Canada, India, and Nigeria were chosen because together they sketch out what Bangladesh’s own path to mechanization could look like, from aspiration to action. Canada represents the future and shows what happens when an entire ecosystem grows around machines: skilled technicians, efficient logistics, and data-driven farming that make agriculture a high-value, high-potential industry rather than a neglected sector. India has a similar agrarian economy of smallholders like Bangladesh, a geographical proximity and similar climatic condition, where the rural economy has learned to share tractors and tools through custom-hiring centres and local entrepreneurs, proving that mechanization can work even where farms are small and budgets tight. Nigeria, meanwhile, provides a parallel developing-country experience, where public–private partnerships and rental-based approaches are helping overcome affordability and access barriers. Each of the countries brings a unique lesson, and together, these examples trace a spectrum from mature to emerging systems, offering adaptable insights for Bangladesh. With its vast rural workforce, growing youth population, and strong policy focus, the country is uniquely positioned to blend these global lessons into a homegrown model of inclusive, youth-driven mechanization.

Build the Foundation: Infrastructure and enabling environment. Rural roads, reliable electricity, connectivity and equipment servicing hubs are essential. Mechanization works when transport is efficient and machines can be maintained.

Ignite an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem: Promote mechanization service models. Rather than expecting every farmer to own a tractor, establish mechanization service providers (MSPs) or equipment–hiring centres. Youth (and especially women) can run these centres — booking machines, dispatching rental services, maintaining equipment.

Invest in 21st-Century Skills: Develop training & skills for youth and women. Equip rural youth with mechanical, digital and service-oriented skills: how to operate, maintain and manage mechanized tools; how to run rental services and logistics; how to handle data/precision farming.

Design for Inclusion: Deliberate Access & Equity. Design mechanization programmes that target women and youth explicitly. For example, Nigeria’s TracTrac service guarantees 50% of new service providers are women. Bangladesh can adopt similar quotas and financing support for inclusive participation.

Unlock Affordable Finance: New Business Models. The upfront cost of machines is high for smallholders. Bangladesh can encourage leasing, rental, cooperative ownership, cluster-mechanization business models. The private sector can partner with government subsidies or financial instruments to bring down costs.

Measure What Matters: Monitor & Adapt. Use data from mechanization pilots to refine models: which crops, which implements, which production systems respond best; track youth employment outcomes, service-provider business viability, productivity gains.

Nahid Tahrima Rashid is a seasoned policy expert with cross-sector experience in Asia, delivering actionable insights on climate change, sustainability, and social equity. She is the Manager of the BL Policy Residency Program and a former 2024-25 Policy Resident.